Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Inconsequential confession: the tie-breaker is rarely a part of the teach at my table. Oh sure, it comes up at some point during a first play, usually as an anecdote of sorts, especially if the gameplay seems tight. Most often it’s a throw-away line near the end because the scoring mechanism does its job with distinction.

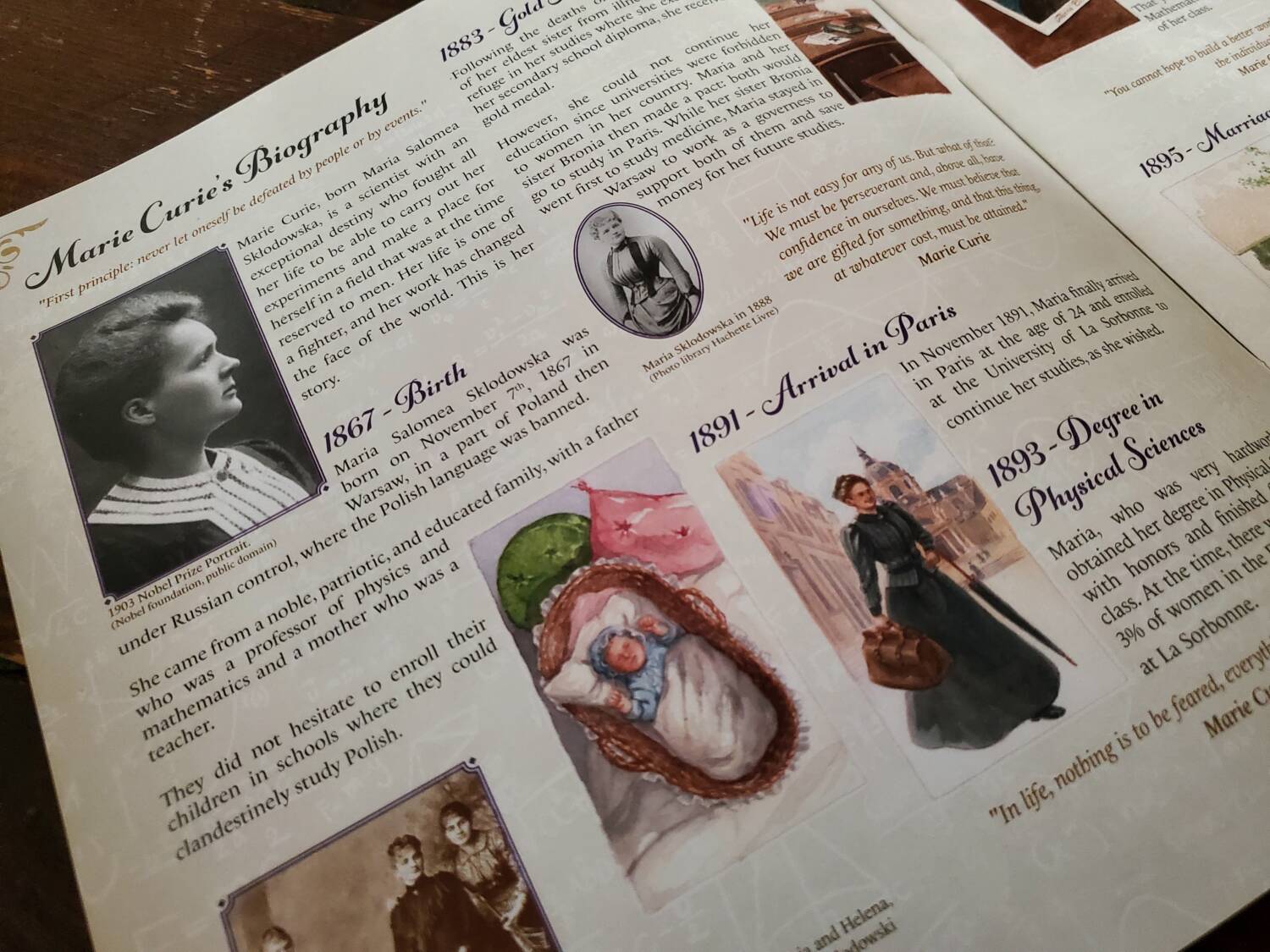

Not so with In the Footsteps of Marie Curie, which chronicles the life and accomplishments of the Polish-born princess of the Nobel prize. Seriously, who wins a Nobel twice? Ok, so it’s been done five times, but Marie Curie got there first for her work in Physics and again in Chemistry. She is best known for her work in radioactivity—and her discovery of Polonium, named for her homeland.

(Note: There has been a fair amount of conversation for years over the tendency outside of Poland to truncate Marie’s name, excluding her maiden Sk∤odowska, which was not her practice in life. Some of the conversation around this game—mostly regarding the title—has demonstrated the same concerns. The game does contain a second booklet on Marie’s life, including her family and Polish origins, which is wonderfully informative even if only part of what many may wish to see.)

In the Footsteps of Marie Curie, from Sorry We Are French and designer Florian Fay, might just be the first game I’ve played where the tie-breakers (and not just one, mind you) warrant bold text, flashing lights, and a small measure of confetti.

The frustration of the tower

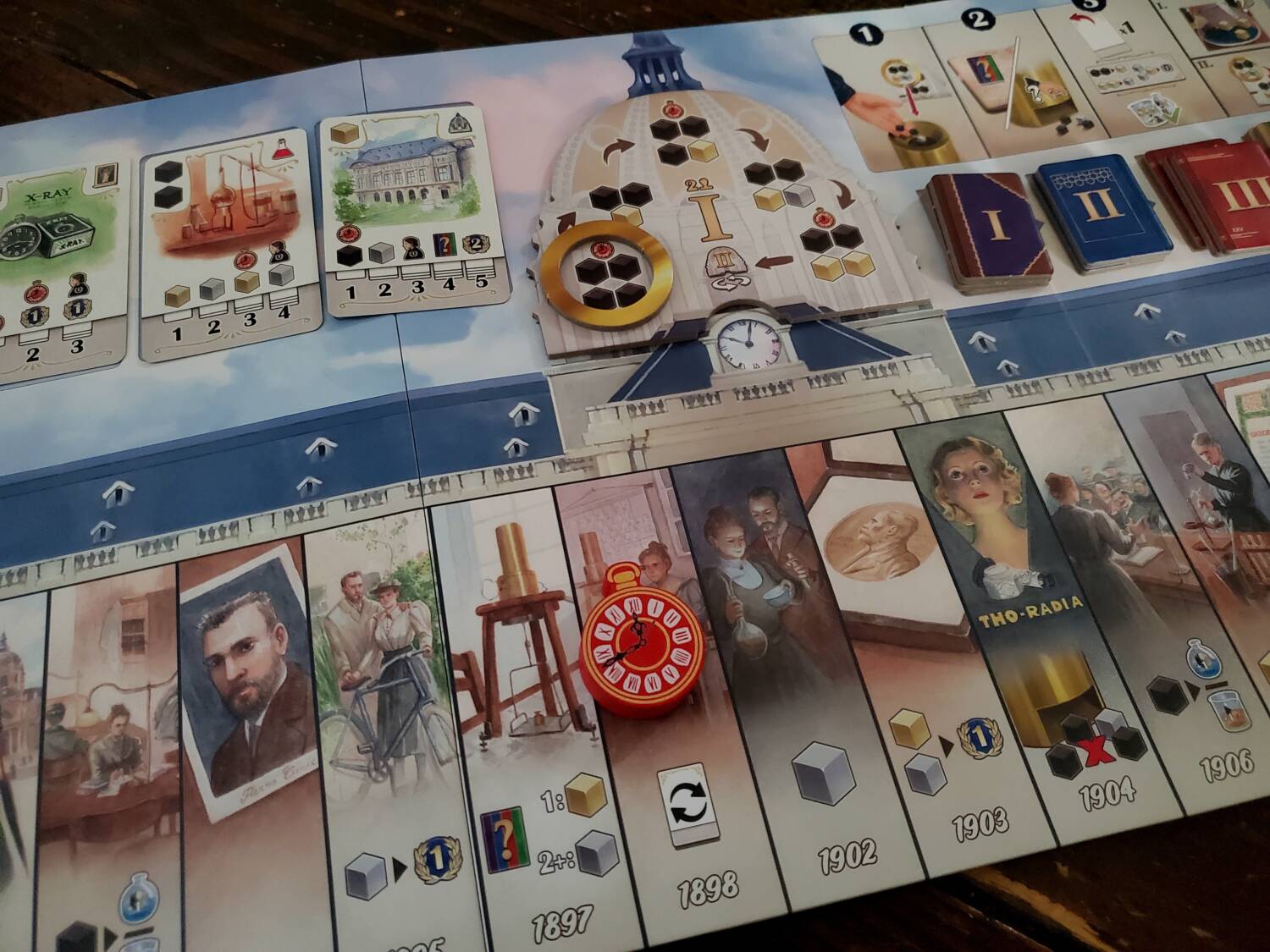

Scanning the table during In the Footsteps of Marie Curie yields a bevy of average sights—cards, chits shaped like beakers and flasks, small cubes, point tokens. But wait, what is that golden tower rising above the fray, you ask? That, my friends, is a tube of delightful frustration.

Every player turn begins by casting a prescribed dose of cubes into said tower. Far from a typical dice tower, however, this tube features a web inside that frustrates needs and desires. More specifically, the web interrupts gravity, keeping cubes from reaching the bottom. As long as players don’t resort to violence, the golden tower will capture and hold upwards of two dozen cubes across the span of the game. Not only does it interfere by withholding cubes, it befuddles by spouting cubes wholly different from those dropped in. Since most turns then continue with the selection of an allotted number of cubes, the frustration is understandable—and, yes, delightful. I love this thing.

Players collect these resources—pitchblende, Uranium, and Radium—in accord with their stock of completed experiments. Thesis tiles await as the alternative, especially when the tower crosses fair designs. Players then spend, utilizing the allowed resource exchanges as needed. Activity cards—available in five suits—grant a boon based on the number and type of cards the player owns. Beakers and flasks expand resource capacities, also giving a point bonus for each completed pair. The entire game operates primarily on these functions.

The grand wrinkle is the timeline of 18 years from the life of Marie Curie. Nearly all the years trigger a game event: a free resource, a conditional resource, or an exchange. The timeline’s stopwatch marker moves any time the matching icon comes up in gameplay. Several rounds will begin with movement (determined by the resource cube map atop the board), and several Activity cards and thesis tiles will also trigger movement. The timeline itself, because it tells a specific story, is static—a thematic gem that will raise the ire of those who prize infinite variability.

The game follows this course of action until the timeline reaches its end, finishing the final round of play. Players then tally points to determine a victor—

Or not

Margin is a fiction In the Footsteps of Marie Curie. Those pairs of beakers and flasks score one point each to a possible total of…three. Each player chases a private goal that is worth either one… or two. Certain Activity cards release… a point once you find four matches or more, which is nearly a fiction in itself. Having the Marie token—reminiscent of the kitty in 7 Wonders: Architects—at the end is worth a point, and there are a few tokens scattered here and there throughout the game.

Bottom line: Scores are low and the tie-breaker sequence holds supreme importance. Remember those cubes? Radium for the win, Uranium second, pitchblende third. Even in my short time with the game, I’ve seen outings decided by Radium and Uranium. That’s more than I can say for most other games in my collection. Managing the tower’s delightful frustration and exchanging resources at opportune moments might decide the outcome.

In a game with so little room for error, the private objectives scream for attention. Every single point is absolutely worth chasing, which sets players off in different directions from the start. Some objectives are definitely easier than others, but they’re all attainable and they all provide solid benefits along the way.

Variability is a tactical cocktail of the five possible personal objectives and the shuffled distribution of cards, beakers, flasks, and theses. Oh, and that tower of—let’s call it curiosity. In the Footsteps of Marie Curie is essentially an exercise in securing nine points. If you reach nine, you’re in the running. I’ve seen eleven, I’ve seen seven. In every sitting, folks seem to get that far via myriad roads thanks to shuffling the bits about, but they are all variations of the same core set of roads.

So far, this has felt good for a family-style game.

For the family

A gaming child can keep up with the rules and options here, making In the Footsteps of Marie Curie a fun title for even the elementary ages. The tower is fascinating enough. The options on a given turn are fairly easy to manage, even if clever plans sometimes elude the youngest at the table. The timeline, despite remaining static, is friendly and rewards a hint of forethought—easier for some private objectives than others. And, if you’re on the cutthroat side, the opportunistic refresh of the card market just might prevent the single point that separates victory and defeat. I suppose a bit of cube counting on the way into the tower might also let on how many Radium are available to pop out.

I would categorize In the Footsteps of Marie Curie as a repeat exercise in juggling knowns. After one play, the game reveals its secrets. Subsequent plays, then, are about handling the timing of release—when will my cubes emerge? Will my cubes emerge at all? When will I see the cards I need? Will it be in time? Which thesis will I pull? If you enjoy this sort of waiting and management game, you might be inclined to like this one.

There’s a lot to like. I’m not sure that the longevity will be there when such similar paths lead to the same destination every time. There are few options for those seeking out a broad and crunchy strategic experience, but there are quirks and enough game here to warrant the price and a season getting to know Marie Sk∤odowska Curie. The Appendix book tells a great story, and the game reflects a life of grand accomplishments. If you’ve ever wanted to be introduced, there are worse ways than a game such as this.