Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I went on a bit of a journey as I considered the place of Ichor in designer Reiner Knizia’s oeuvre. My first thought, the one that came to me instinctively, was “Knizia doing an abstract game? Interesting.” My operating definition of an abstract game is relatively narrow. Rather than considering any game that does not have an explicitly implied—I’m not sure “explicitly implied” is possible, but I’ve said it, so here we are—story or setting “abstract,” I only refer to games in the wide family of things like chess, mancala, or Santorini as “abstract.” For my personal heuristic, there seems to have to be determinism, movement of pieces, and some heavy spatial reasoning.

My second thought was, “What a stupid thought. If anything, it’s surprising he hasn’t done more of them.” Knizia’s games are nearly always abstract, or at least abstracted. We could get lost in the weeds of “All board games are abstracted,” but I’m not interested. Application denied. Some games strive for a relatively representational approach to their setting. Terraforming Mars has you accrue resources to develop technology and build settlements on Mars. Other games don’t. Lost Cities is about playing cards in increasing order. It is also somehow about archaeological expeditions.

Knizia’s games tend to fall into the latter category, so heavily abstracted that he is often accused of pasting themes onto raw systems. He has said over and over again that this is not the case, and I personally believe him about one-third of the time. One of my deepest-held board gaming beliefs is that Lost Cities is more successful at evoking the emotional space of an archaeological expedition than most games are at evoking whatever emotional space they’re aiming for, but we’re getting off track.

The point is, Knizia’s games already feel heavily indebted to abstracts, whether you define that term narrowly as I do or broadly as do the fine people at BGG (Through the Desert an abstract? Really?). His games are mathy, they’re a little territorial, the rules tend to be as minimalistic as possible. It’s a natural fit, and it’s weird he doesn’t have his own GIPF Project.

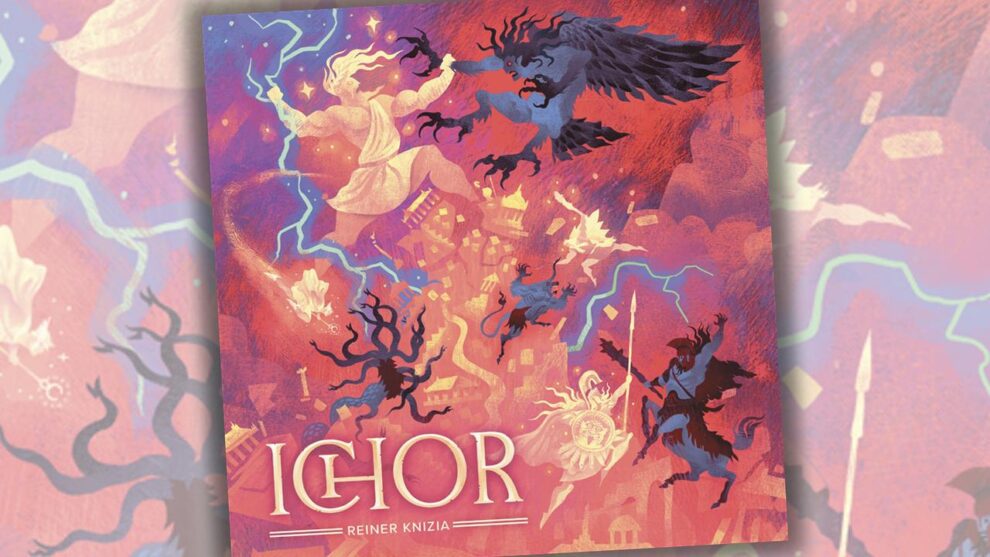

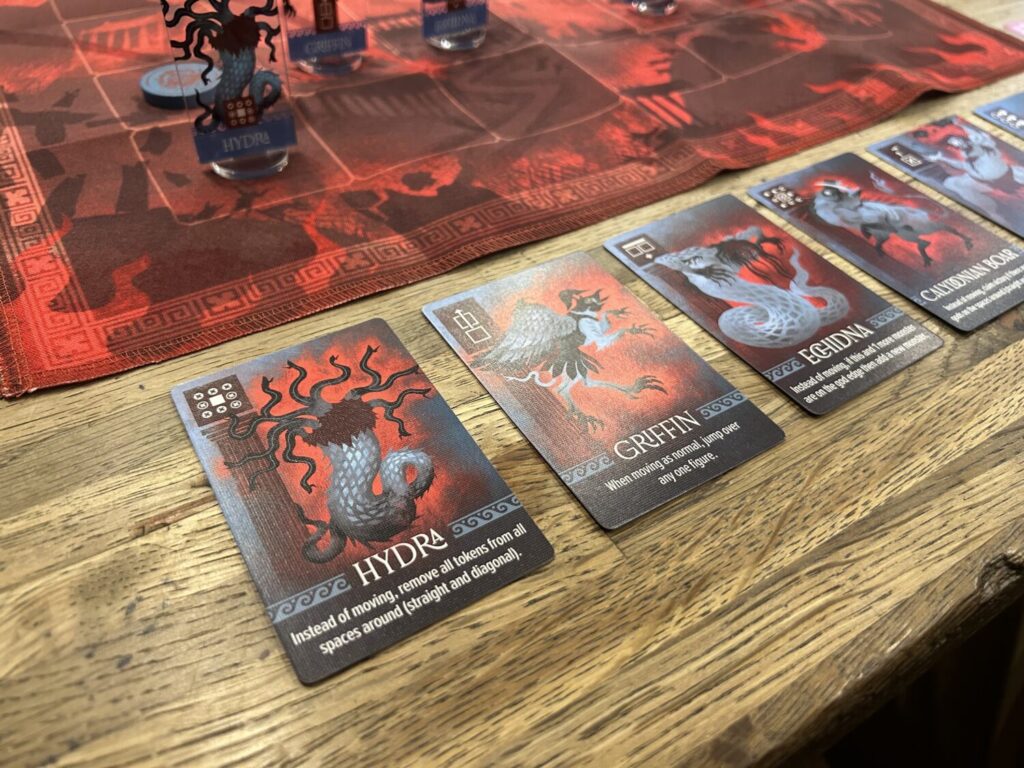

He does, at least, have Ichor, in which Greek Gods and equally-as-Greek Monsters face-off with one another in a race to shed tokens. The two sides begin with six pieces on the board, and the players take turns moving them orthogonally, stopping only when they want to or when an obstacle—either another piece or the edge of the board—gets in the way. The player puts one of their tokens in each of the spaces their piece passed over. If any were previously occupied by an opposing token, they get replaced.

Each of the player pieces has a unique, single-use power. Artemis, for example, can move into a space occupied by a Monster and remove both himself and the creature from the board. Geryon lets you add two more tokens onto a space you added tokens to during that turn. Poseidon wipes his column of tokens. These sorts of things. I emphasize that these powers are single-use, because a huge part of what makes Ichor tick is judging those moments when you should let loose one of your six arrows.

As much as I love positional abstracts—and I do—I can’t quite get into this one. It brings to mind Bilbo Baggins’s beautiful insult, “I like less than half of you half as well as you deserve.” I can tell Ichor is good, with many admirable qualities, but it doesn’t quite resonate with me.

I think the issue is YINSH, one of the games from Kris Burm’s aforementioned GIPF series. First released in 2003, I think it’s fair to say that YINSH is the best known of the bunch. It’s certainly my favorite, though DVONN is right at its heels. You take turns moving rings around a spiritually hexagonal board, leaving and flipping tokens until either player has produced three sets of Connect 5. It is dynamic, tactical, tactile, and rewarding.

In YINSH, thanks in large part to its radial movement, the board is wide open and becomes more so as the game proceeds. There is a feeling of constant progress, even if it is progress in a direction for which you do not care. Ichor, with its orthogonal movement and narrow lanes, is about restrictions. It is meant to be a crushing, grinding exchange of tokens as both players seek to eke out a slight advantage. The powers of the Gods and Monsters are intended to momentarily snap those restrictions, and it is incumbent on the players to figure out when to deploy them.

To my mind, these are two regional variants of a similar dish. Ichor isn’t far enough away from YINSH to avoid tasting like NOT YINSH, and so I spend my time with Ichor wishing I were playing YINSH instead. I cannot quite separate the experiences. Don’t let this dissuade you, though. Even if you love YINSH, you may love Ichor. If you don’t love YINSH—impossible—you may love Ichor. It won’t be entering my personal pantheon, but it’s a good game all the same.