Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

In looking back at my review of General Orders: World War II, I was surprised to see that I’d given it 3.5/5 stars. Feels high. My opinion of the game hasn’t exactly soured over time, that’s a bit strong, but I never reached a point where I got much enjoyment out of it. Play after play, it was a design that floated on the periphery of working without ever quite crossing over. As much as I loved the idea of an approachable and quick-playing war game in a small box, General Orders: World War II didn’t do it.

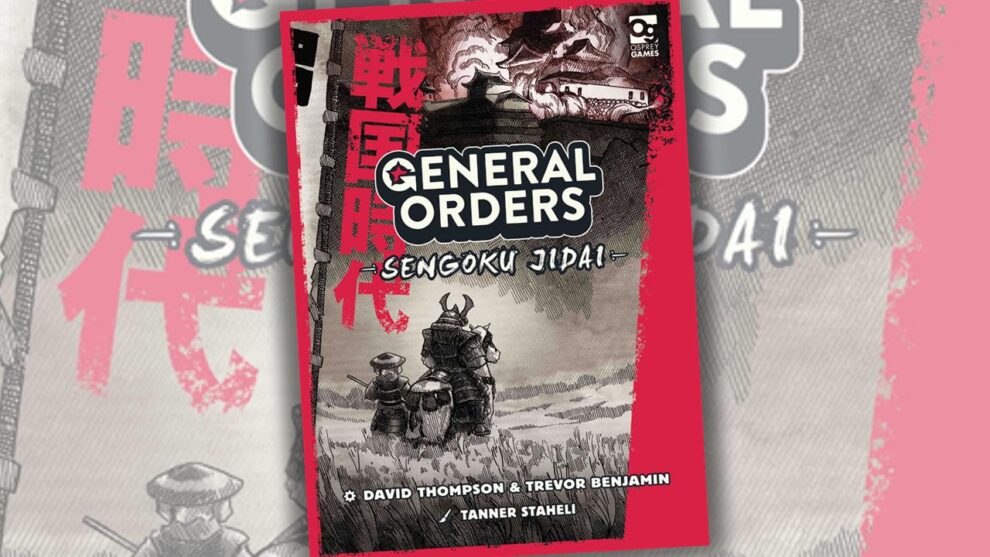

I was ready to pass on the follow-up until I saw the box: I’m a sucker for sengoku-era Japan, and I love a boat. I’m a simple man, you know? And sometimes that works out! David Thompson and Trevor Benjamin’s burgeoning series deserved another airing. General Orders: Sengoku Jidai improves on the original in just about every way imaginable.

Boats

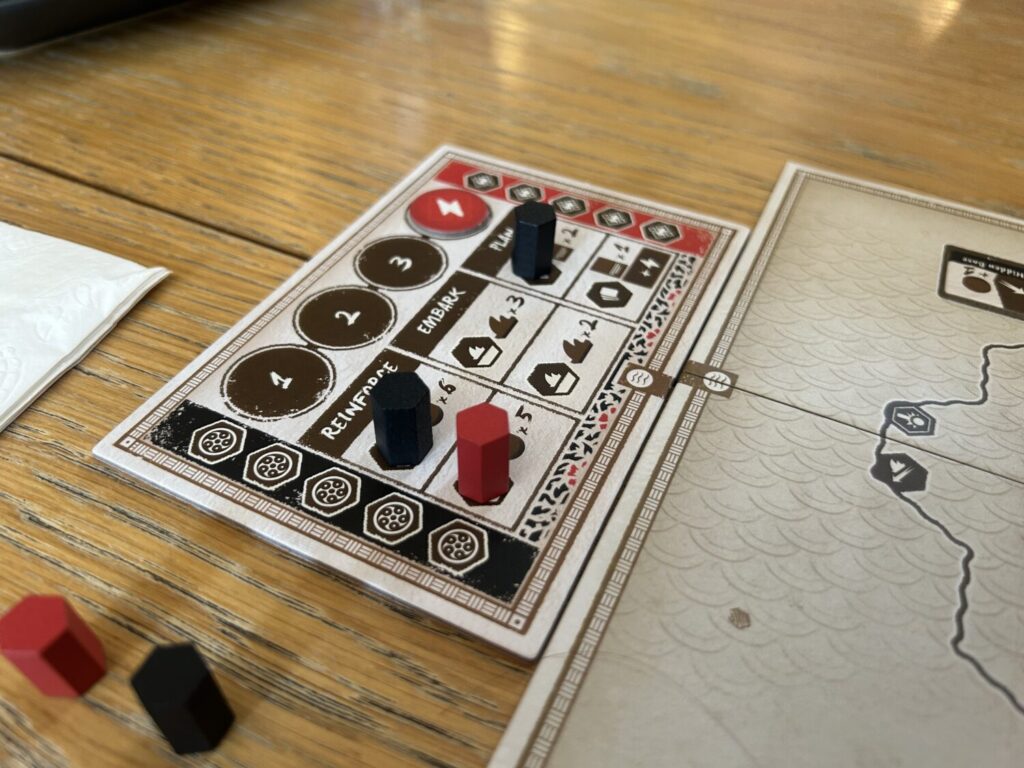

I think it’s the boats. It has to be. That’s the only major change that separates Sengoku Jidai from its predecessor. The core rules are identical. This is war gaming via worker placement. You take turns putting one of your five Commanders on any available action space, and perform the corresponding action. Move troops. Deploy reinforcements. Draw cards that can be used to modify other actions. Combat is automatic and largely determinative. You win either by taking control of your opponent’s headquarters or by controlling a greater share of the positions worth victory points at the end of the game. If you’ve played World War II, this paragraph is giving you déjà vu. It is all, fundamentally, as it was.

Other than those boats. They serve three functions: they are units in their own right, controlling positions worth points at the end of the game; they are military units, capable of firing their cannons on adjacent spaces; and they are infrastructure, allowing for the movement of troops between islands.

The flexibility of those boats makes the whole design much more engaging. Plans are less readily transparent. The intention behind any given move is obfuscated. Is my opponent moving those troops because they want to hold that position, or do they want to launch a boat from the dock, or do they want to use the artillery there? Have these boats been moved to attack? How aggressively will they fight to hold that space? It’s just so much better.

Across five or six plays of World War II, I never experienced a moment of drama, a sense of tension, a surprising move. My first play of Sengoku Jidai was filled with them, and the end of the game was the culmination of plans played out over the course of the entire game. Neither player could believe how it all played out. Whatever Thompson and Benjamin changed, it is working.

Across five or six plays of World War II, I never experienced a moment of drama, a sense of tension, a surprising move. My first play of Sengoku Jidai was filled with them, and the end of the game was the culmination of plans played out over the course of the entire game. Neither player could believe how it all played out. Whatever Thompson and Benjamin changed, it is working.

Combine these tweaks with a gorgeous box—love that red—and wonderful art from Tanner Staheli, and Osprey Games is onto something. I have no idea how many more installments are in store for this series, and I have no idea how robust this formula will prove, but with General Orders: Sengoku Jidai at least, a promising design has been made into something so much better than I anticipated. I love it when a design comes together.