I don’t sit down to complex games more than a few times a year at this point. I rarely have time for a three- or even a two-hour affair. All current habits aside, though, I’ve been waiting for one bloated box to arrive at my door. Ada’s Dream has been in the back of my mind for the last year. The anticipation never faded, which is never a guarantee for a crowdfunded project. I put it to the table with my wife and two dear friends almost immediately, and I’ve lived to tell the tale.

Studying Ada

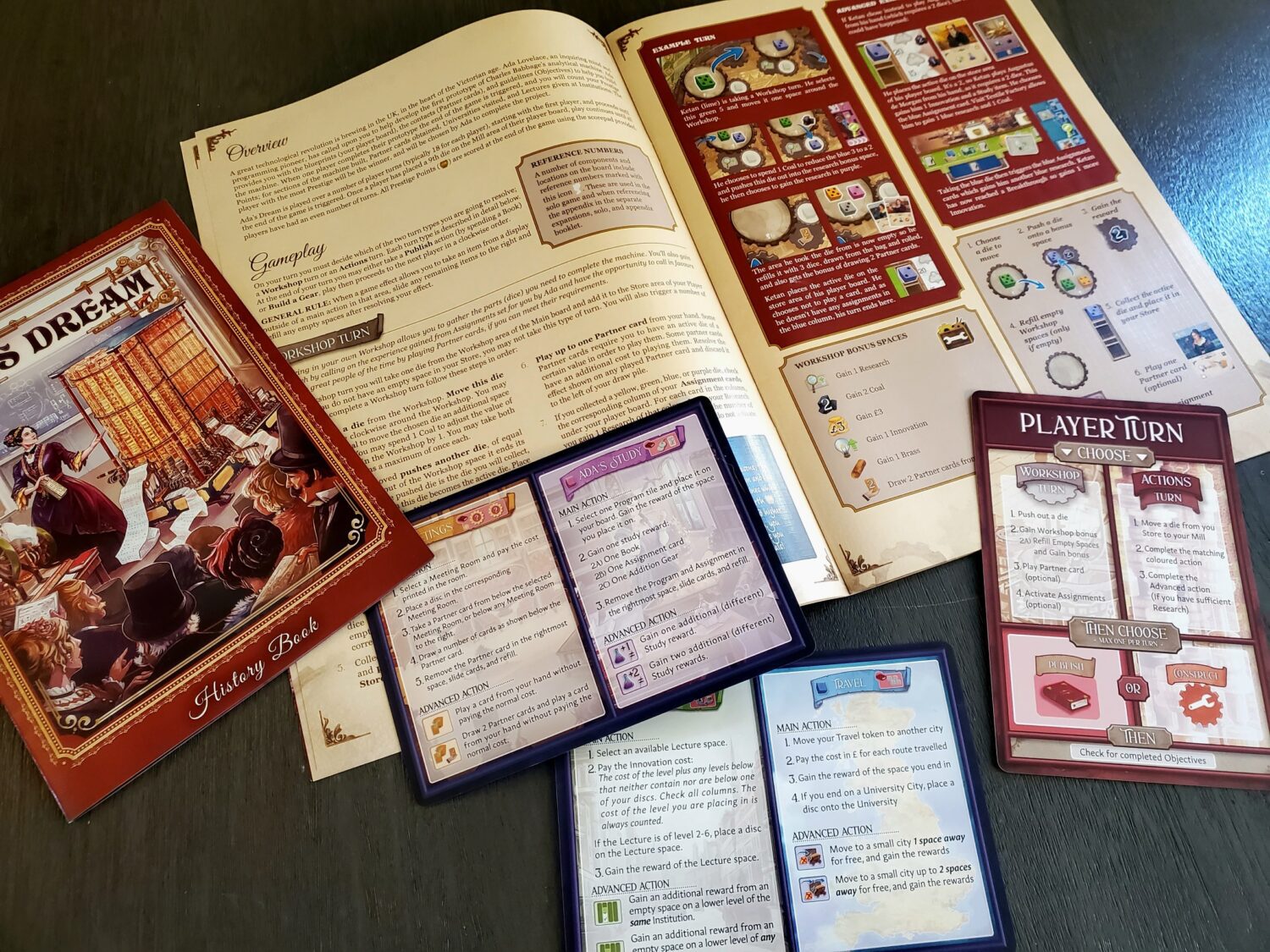

Because this release is hot off the presses as of this review, it is not supported by a wealth of online video content for learning the finished system. Thank heavens, then, for the editorial team at Alley Cat. The real dream of Ada’s Dream is the rulebook. This thing is wonderful—thorough and wonderful. I read it several times prior to teaching the game, and we referenced it repeatedly throughout the first play for added clarity. Whether I or one of my companions went hunting, though, we found answers swiftly and without difficulty. We finished the game having made only the smallest of mistakes. The book is well constructed, well organized, and, well, beautiful.

I managed to teach the game in just shy of a half-hour with only the Player Aids in sight. The aids are also excellent, which is good because there was nary a turn where players’ eyes weren’t glued to the oversized cards every step of the way. The iconography is clean, intuitive, and printed everywhere that it matters. The design is, overall, very approachable.

The Player Board

I backed the mid-grade Deluxe edition—fancy resources and expansions, but no metal coins or neoprene mat. No matter the version, though, there are elements of the production that are outstanding. The main board, for example, laid flat out of the box and is complete with indents/recesses all over to help contain the discs. I am impressed with the production.

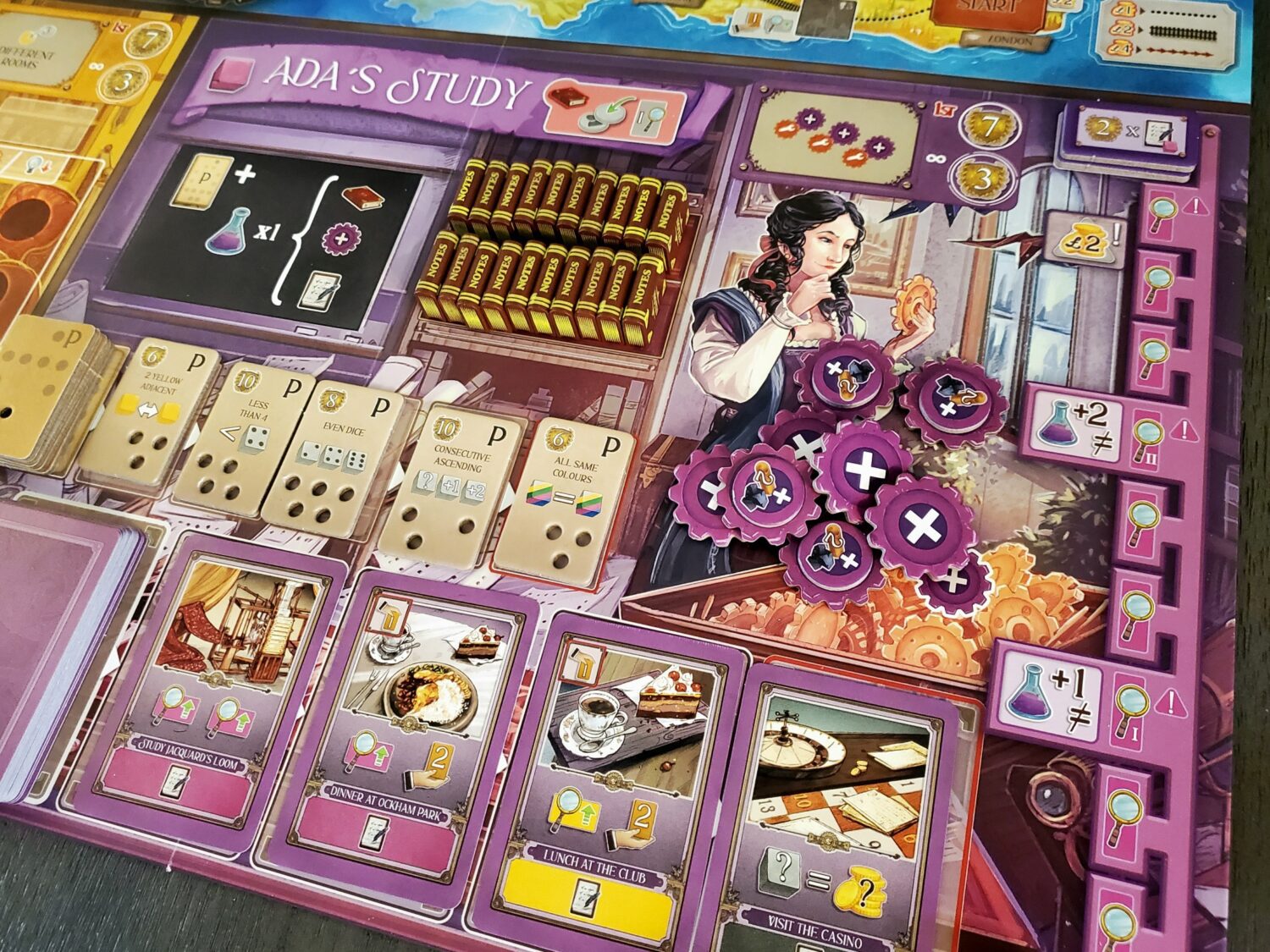

The double-layer player board is the centerpiece of the game’s scoring engine. Players are building a 3×3 calculator of numbers (dice) and base mathematical operators (gears). The grid, called the Mill, mimics the prototype Analytical Engine for which Charles Babbage is famous. Players each create their own efficient rows and columns of calculations. At the game’s end they trigger from top to bottom and left to right (modern order of operations is not in sight in the mid-19th century—sorry PEMDAS fans) to produce a hefty percentage of a player’s score.

Along the way, players also collect Programs—punched tiles that dictate unique rules for the dice in each row and column à la Sagrada. The slots along the grid allow the programs to stand upright, keeping them largely out of sight of the other players. The variety of punched holes adds old-timey computer charm to the component. These first two scoring elements are responsible for 60% or more of a player’s final output. The player board is enormous (the entire game bears generous proportions), but it provides a highly organized and gorgeous home base.

One hindrance adds the final layer of tension to the player board. Each of the recessed locations where a player wants to construct a mathematical operator is occupied by a disc at setup. These discs are the markers for use across the central game board and must first be removed before any calculations take place. In fact, they serve as 3D reminders of the endgame penalties for failing to install the machinery. Even the most clever dice placement can fail without a vacancy to place the gears.

The Central Mechanism

Half of the turns in the game take place on the dice rondel, the means of collecting dice for the Mill—the grid on the player board. The mechanism is interesting. Players move a single die from any of the six pods clockwise to the next pod. Once the die arrives, it pushes out another die (of equal or lesser value) that the player will collect. Each pod comes with a bonus of goods or services—coins, coal, brass, cards, track movement, innovation, etc.

Every decision on the rondel is driven by the desire for a number to feed the calculator, a color to feed a Program tile, and a bonus to feed the coffers. As an added consideration, if a die is taken that empties a pod, the player receives another bonus, a bonus bonus if you will, from the emptied location. Sometimes you take a die just to get the most stuff. There is one more crucial layer to this decision, but that’s the next section.

At first blush, you might think players just want the highest dice to make that calculator sing high numbers, but it’s not so simple. Each player has two gears bearing a minus sign, so there is a place and a reason to drop a one in the corner. Certain Programs require numerical specifics as well, such as ascending or descending order, which creates a more numerically broad landscape. Plus the game is loaded with opportunities for dice manipulation, both at the rondel and in the Engine, leaving the strategic door wide open to take sub-optimal dice with plans of rectification. To top it off, players also have to generate steam to raise the ceiling for their calculator, otherwise the labor of harvesting big numbers is all for nought.

Did I mention there are things to think about?

After players collect a die, they can optionally play a card from their hand—a partner with a quick benefit. Players maintain and massage a hand of cards throughout. In a way, it feels like a deck-builder, but the total card count is a static eight, so the deck is being refined rather than built. New cards enter, forcing other cards out.

The Actions

Claimed dice sit in the Store, the player board’s waiting room of sorts with three slots. The other half of the game’s typical eighteen turns are spent moving a die from the Store into the 3×3 grid, unleashing one of the game’s four Actions, dictated by the color of the die (the crucial layer mentioned above). Each of the Actions then functions according to a unique protocol in one quadrant of the central board. Each area features a bonus track along the side. As players move up these tracks, the Action areas grow more potent with additional activity.

Ada’s Study—the purple die—is where players gather goodies that directly feed their player board. Program tiles, Addition gears, Notebooks, and Assignment cards. I’ve not mentioned the Assignment cards just yet. They also inhabit the player board, where they not only shower instant boons but also grant movement on those bonus tracks each time a matching die enters the player board. Don’t worry, it’s all on the player aid.

The Meetings Area—the yellow die—is where players court assistance from powerful people via cards. The Area is divided into four rooms, each with only four spots for markers. Players select a room, place a marker from the player board, and select a card. Each room is a mini area-control battle. At the game’s end, rooms bestow point tokens that reward the “types” of partners on the cards for scoring. Since players only have eight cards at a time, the Meetings area becomes a place to hunt the most lucrative or necessary benefits while also trying to optimize the right set of “types” to score points in the end.

The Institutions—the green die—are a series of four graduated tracks where players “listen to lectures” to collect rewards, moving up and across the tracks. The rewards are varied and potent, and since each reward is only available once, there is a pressure to reach locations first. It was surprising, even in the first play, how often players were eyeing the same reward at the same time. The design seems to anticipate certain needs in a way that pits players in the occasional mini-footrace. Timing is definitely a factor.

The Travel Map—the blue die—is a map of the British Isles that players navigate freely, limited only by the cash they are willing and able to spend to move by road, rail, and ferry. Small towns grant small rewards. University towns grant larger rewards and—more importantly—allow players to place one of the markers from their board to lay claim to endgame points.

The Actions are sensible with the game’s narrative. The steps, also, are sensible. But every Action has its own procedure and its own bonus structure. Your first play will be a constant reference to the Player Aids and the rulebook to make sure the necessary steps are taken and the earned rewards collected. With only nine Action turns, it could be beyond the mid-point before a player gets around to one of the Actions. For a first play, this delay is catastrophic for an ailing memory like my own.

But by the home stretch, these turns feel like a roll-and-write game, juicy cascades of Actions, extra Actions, and gobs of bonus considerations. Once the Actions make sense, visiting the Workshop to collect dice bears even more weight. Every die selection is a bonus to collect, a number to calculate, a Program to gratify, and an eventual Action protocol to consider. There are no hollow decisions in Ada’s Dream, and it will take the bulk of the first game before the big picture and the minutiae click into place.

So the basic turn is, essentially, either the Workshop rondel or an Action. After following the protocol, there is one final decision, regardless of the first selection. Players can Publish, spending Notebooks for special action based on their turn choice, or they can Build, paying to install a calculating gear in their player board (provided they’ve cleared a space). One decision, followed by one protocol, followed by another decision. Eighteen times.

Time keeps on ticking, ticking, ticking

Let’s stick to the math. If four players sit down for eighteen turns each as we did, that’s seventy-two turns. (Side note: it is possible to have more than eighteen turns, but players would have to conspire—foolishly?—to do so.) If a player’s turn takes one minute, that’s seventy-two minutes. Two minutes? One hundred forty-four. You see where this is going. Your first play will have some five and seven-minute turns as players learn the various protocols. Pack a lunch. Pack a dinner. We sat for four hours with Ada’s Dream.

Now, that being said, a two player game with two-minute turns is less than 90 minutes. I expect my wife and I will mostly engage this one as a two-player game, which means we will eventually reach the leanest experience. We are planning to play it again in a week or two with the same foursome, though, and I expect cutting the time by 30% or more since we are now familiar with the flow and aims of the game. But if your group is prone to locking down in analysis paralysis, bring a side game to kill the time. You can probably squeeze in a game of Azul Duel or Everdell Duo with the player across from you with four at the table.

I wasn’t bored with the downtime, though. By mid-game, it’s best to have a Workshop turn in mind and at least an order of preference for your available Actions. As a result, mental gears are always turning, considering, and adjusting as players inexplicably take the one die you wanted or slip into an Action area to grab the bonus you had set your heart upon. Planning matters here, so the downtime is not wasted.

The spice of life

Alley Cat packed Ada’s Dream with variety. Each Action area has an objective for players to race after. The board is printed with base experience objectives, but there are balanced stacks of tiles in the box to shake up the chase from game to game. The Travel area comes with unique University city tiles to change up the rewards on the map as well. Players begin the game with seven identical cards, but also one unique card each to lend asymmetry. And, let’s face it, with dice at the heart there is always variety and forced flexibility.

The consensus among our foursome was that Ada’s Study is all but essential as an early priority for players. She provides resources—addition gears, Program tiles, Notebooks, etc.—that directly impact the all-important endgame tally on the player board. There are ways to gather the resources elsewhere, but not with the same speed and regularity.

But among the other three Action areas, there is nothing so clear cut. Players who chase Meetings can dominate the area control and its end-game bonuses. The card collection is not the most lucrative for endgame scoring, but pushing the bonus track actually allows playing a card with every visit, turning a so-so card grab into a cornucopia of possibilities.

The Institution tracks unleash their bonuses in waves, chasing ever-increasing output along the way by spending Innovation. Moving up the bonus track eventually makes one turn feel like two, and players who dominate here also receive endgame bonuses that incentivize return visits.

The Travel option feels the most customizable. Having the ability to reach any spot on the map (for a price) at least opens the door to late-game possibilities when a very specific combination of effects are necessary to complete plans.

Our scores were fairly even by the end, and we were all chasing different areas and objectives. The winner in our game never visited one of the areas, and nearly neglected another. All this says to me that there are different ways to win. I like that, even if it takes a small correspondence course to prepare for the first play. Of course, the winner had the most complete set of Programs, and a pretty slick set of calculations on her player board.

I really like it

Because of the preparation I had put in for the teach, I think my turns were the shortest with our crew. I did not win (which is not often my top priority). My turn length matters at this point, because it suggests that we can play Ada’s Dream in a reasonable amount of time. My first play of Boonlake lasted slightly over three hours (with two players). My first—and only—four-player game of Obsession exceeded three hours, too. But those titles have grown more and more manageable with each successive play. In fact, they’ve become rhythmic. None of them have reached the time on the box (which, I believe, is as much a fudge-fest as the age recommendation—always a consideration when judging a game by its cover), but our familiarity and comfort have allowed us to enjoy them reasonably.

I love the decision space of Ada’s Dream. I love balancing the timing—when to draft dice and when to take Actions. I love watching other players, anticipating the priority of their available Actions to predict the timing of my own. With a bit of downtime in the learning curve, I was also learning how to be attentive to the strategies in play.

I love bonus tracks and the combo-rific chains of rewards. And, because I’m twisted, I love the math of the Mill. I want to build a calculator. I want to program patterned rows and columns, even if I’m not that good at it, because when plans work, they really work out. I want to sit with my family and friends for as long as the game takes, so long as they’re enjoying themselves. I was ready to dive back into Ada’s Dream as soon as we stood up—at midnight.

Addendum

After writing these thoughts, I played one more time. We introduced the game to two more friends. My opinions here have only grown stronger. I was able to teach the game more completely, and, as a result, we spent significantly less time in the rulebook. Two of us knew the game, so we were able to answer questions and provide clarity. After the teach, we were just over three hours—a significant improvement. Our friends had been through a late-night affair with Horseless Carriage the week before, so Ada’s Dream felt light by comparison.

In both plays, first impressions have been positive. The colorful aesthetic, the hefty boards, and the solid resources provide a nice greeting. The decision space is wide and deep. The introductory experience is long, but promising. I have high hopes.

Once I have more plays under my belt, I’ll aim to revisit this review. It may be a while, but perhaps I can even get the Great Exhibition expansion to the table. I’m not likely to engage the solo mode, but it’s in there, too.

My initial reaction? Kudos to Toni López for the narrative design and game flow of Ada’s Dream. Kudos to the team at Alley Cat for the stellar production value. Kudos to Javier González Cava for the beautiful artwork. Who knows how I’ll feel after a dozen plays? For now, I have a title to explore, and, by golly, a calculator to program.