At Essen 2025, I picked up a review copy of Kingdom Legacy, the latest release from Swedish design Jonathan Fryxelius and publisher FryxGames. I hadn’t heard anything about it prior to the convention—nothing drives home the vastness of our ecosystem like counting the games at Spiel that you’ve never heard of—but I was intrigued by the idea of a solo six-hour legacy game no larger than a standard deck box. I wanted to know how it worked.

Curiosity is a powerful motivator, and solo games are easier to table, so Kingdom Legacy was the first game I played when I got home. I spent a good amount of time with it and would love to write about my experience, but that is a review that will never be written. After an hour or so of playing, I realized that Kingdom Legacy uses AI art, and we here at Meeple Mountain have drawn a line in the sand when it comes to AI-generated material. When a publisher fills out the review request form, one of the provisos reads:

Note: Meeple Mountain does not review games which use AI generated artwork or content. If we discover that a game uses AI generated artwork or content in their final product, we will decline to accept a review copy or, if a copy has already been received, decline to publish content for that title. By declining to review a game we place no value judgement on the game itself, the designers, or the publishers.

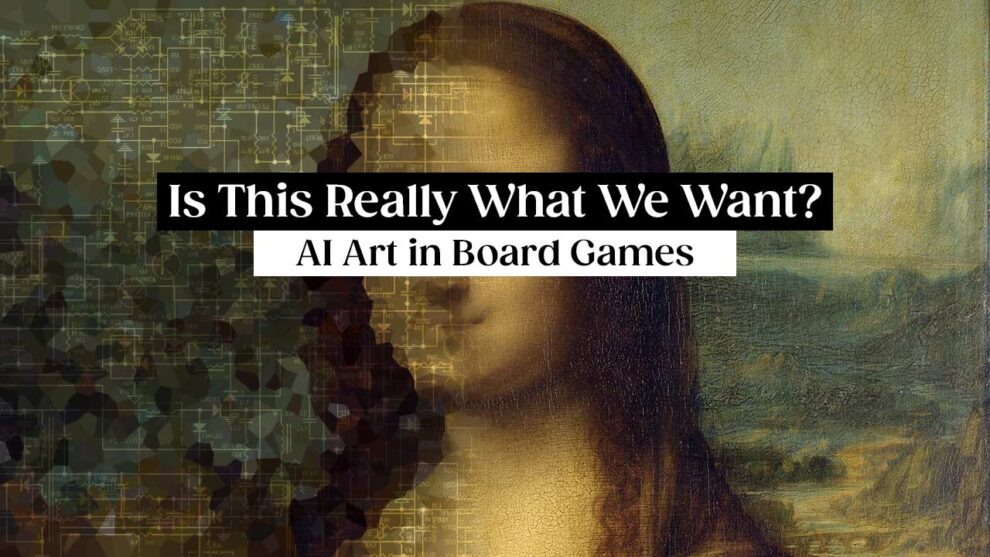

We have absolutely covered at least a small handful of games that use AI art, but never knowingly. That qualifier is becoming more and more precarious, as it becomes increasingly difficult to know. Not that Kingdom Legacy is going to throw anyone off the scent. It bears many of the telltale signs of AI art: a high-saturation cover image that looks like Jolly Ranchers taste, anatomically aberrant hands, stylistic inconsistencies between images, a complete lack of personality or individuality, etc., etc. But—but!—this art could pass for the real thing if you weren’t paying attention. Do the cards look good? No. This is the sort of generic and passable art that reached its zenith on the covers of high fantasy mass-market paperbacks published in the 1990’s.

While I do intend “generic and passable” to be derogatory, we also have to acknowledge that there’s a sort of compliment in there: AI art has achieved the basic requirements of generic and passable. Even a year ago, that wouldn’t have been possible. If we limit the scope of this conversation to AI illustrations—LLMs, AI audio and video generators, and the use of AI tools to create photorealistic images are separate, significantly more urgent existential issues that I won’t be talking about on a website for board game criticism—and if we can agree that the raison d’être of AI art is to create passable art faster and for less money, then it should hardly be controversial to observe that AI is getting better at what it does.

That isn’t to say that we all agree on whether or not this is a change for the better. I am sure we don’t, since even individual members of Meeple Mountain don’t have the same opinions. That is precisely why we must have this conversation, both as an industry and as a hobby. Now is the time to decide if AI is welcome in the world of board games, before it becomes so good at what it does that it becomes invisible. At that point, without enforced community standards and norms, it will have gained enough of a foothold that everyone takes its presence for granted. There are many reasons we believe that AI should be granted no quarter within The Hobby™.

There are environmental concerns, which are both well-founded and well-documented. The surge in AI over the past several years has led to an unprecedented uptick in the construction of the data centers that host the servers that churn out the result on the other end of any user-provided AI prompt. Data centers are not unique to AI, and have existed since the 1940s, but the economic frenzy around AI has injected steroids into the demand both for and on them. They are using more and more electricity, more and more fresh water, more and more land, and they are causing more and more pollution in their local communities. MIT Technology Review did a phenomenal and approachable long-form article digging into AI’s energy use if you want to learn more.

With AI art specifically, the energy use gets intense. According to another MIT Technology Review article from 2023, generating a single image through AI uses about as much electricity as is required to completely charge your phone. This issue is complicated contextually by the fact that professional artists also do their illustrations on computers. A similar amount of electricity—possibly even more—is used by a human and their computer over the several hours necessary to create a single finished image. But what’s unambiguous is the water: a single ChatGPT conversation famously uses up enough water to fill a typical water bottle, and an image will use even more. The only water Vincent Dutrait uses when he draws is the water he’s drinking, and we can agree that’s sort of the point of water.

Modern board games are already an environmentally precarious hobby, based as this all is on ravenous consumption, production, and shipping. The hobby is making good steps to address these issues, as we start to embrace packaging without shrink-wrap and return to recyclable components. The environmental impact of AI would be an unnecessary technical foul, undoing much of the good work publishers have done.

Then there are issues surrounding the position of artists in commerce. To use AI art is to take jobs away from skilled artists, who I can assure you are already struggling to find work that respects the value of their contributions. Worse than that, these jobs are being eliminated and the same tasks are being performed by software that was illegally trained on the now-unemployed artists’ work. AI firms proft off the work of others. AI is the ship, and its adherents are the pirates.

For some, the elimination of The Artist is an argument for rather than against AI. Why pay a few thousand dollars for a team of artists when you can pay a nominal subscription fee to remove watermarks? The consumer, too, could benefit from this, the argument goes. A game like Kingdom Legacy, which sells for around $20, would probably have to sell for significantly more to cover those extra costs. And does AI not represent a great democratic leap forward, into a world in which the ability to “draw well” no longer acts as an ableist gate-keeper?

Personally, as a consumer, I would rather pay the 5-10 additional dollars to have an experience that makes me feel like there’s someone on the other end of the line. AI can paint you a barn, but it cannot imbue that barn with personality the way a good artist can. There’s more character in Sylvain Leroy’s icons of wheat, tomatoes, and pickles in Formidable Farm than there is in all of Kingdom Legacy. AI wouldn’t add the occasional dead panda to the camel cards in Jaipur, or, at least, it wouldn’t do so in a way that made sense.

And as for the latter argument, that AI will allow more people to realize their dreams? Please. The joy in creating something is in having created it. If you put a game review down in front of me that I had no memory of writing and you told me it was mine and you told me it was great, I would have no response to that other than confusion. It is the years of practice, the active parsing of arguments and choosing of words, the time spent on thought and on writing itself, that makes having written something meaningful. This is just as true of visual art. I would rather play Kingdom Legacy with a bunch of absurdly rough line drawings done in Sharpie, and I imagine that’s true of a lot more people than you might expect.

Even publishers feel that way, at least in the early stages. AI has thus far found its greatest use-case in designer prototypes, but publishers are less enamored than many designers might expect. One development team told me, “We prefer that the art is kept to a bare minimum. Too much effort on that front makes us wary that the designer is attached to this aspect of their prototype. Most of the time, it’s bad and only distracts from the core concept.”

As I contemplated Kingdom Legacy and the larger conversations it represents, I found myself over and over again returning to the same simple question: Is this really what we want? Art of every variety is meaningful because it represents a series of choices. Not necessarily conscious choices, but choices nonetheless. This is why criticism of any form exists, why books resonate, why movies are fun to pick apart shot-by-shot, and why games are worth consideration. They are all, each and every one of them, made up of a series of choices by the people involved in creating them. Would you sit down and play a game as anything other than a curio if you were told “The rules for this were created by a computer algorithm that doesn’t understand what any of the words mean or how the order and relationship of those words might create an emotional experience for the players at the table, instead creating its product via probabilistic word selection”? That sounds awful. Why are we at that table?

AI does not make choices. AI doesn’t have a sense of humor. It cannot be mischievous. It cannot create something that is intentionally frightening, or sad, or joyous. That is because it cannot create intentionally. AI art exists to be a simulacrum. It has no other purpose. It does not mean to create things we have not seen, and it has no ability to reflect the world in any meaningful sense. To replace a human artist with a generative computer algorithm is to admit that the art itself has no value. If that were the case, then why do publishers spend so much of their budgets on art that will grab the customer’s eye, that will evoke a world? If that were the case, even if you agree, then hell, let’s have Jonath Fryxelius take a stab at illustrating that deck with Sharpie. You don’t care anyway, right?

It is precisely because these things are meaningful that we are here. Games are not great because they exist. They are great because of the people who make them, and the people who play them. The illustrators and the rulebook writers and the copyeditors and the proofreaders are just as important to the process. To not use the former is Mr. Fryxelius’s choice. To not cover his game is ours. It may well be that we are doing no more than forestalling the inevitable. Certainly, our policy on this matter changes nothing in the grand scheme of things. But a line in the sand has a value all its own. It is a declaration of what you know to be right and what you are willing to compromise on. I would rather stop buying and writing about board games altogether than surrender play to the machine.