Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Thing Thing isn’t a great title. Don’t get me wrong, it makes me laugh, but it’s a shallow laugh. An almost annoyed, perfunctory exhalation of air. An acknowledgement that what we’re doing here is cute, but my delivery of “cute” involves tight mouth corners. Thing Thing is a title that somehow manages to be both memorably silly and entirely anonymous. It doesn’t sound like the name of something so much as it sounds like what you’d say when you’re trying to think of the title, which is almost certainly the point.

Thing

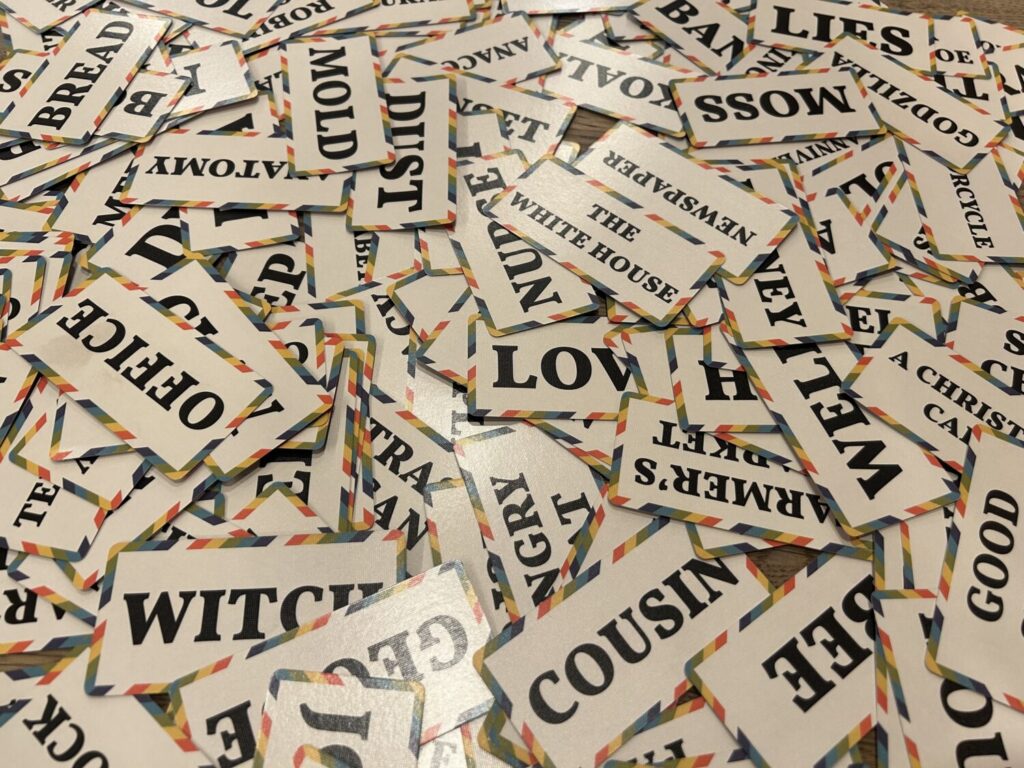

Each player is dealt a hand of cards, each containing a single word or item. Like Apples to Apples, Thing Thing is a word game based on association, but it inverts the formula. In Apples to Apples and its various progeny, you choose the card from your hand that you think best suits the category on the table. In Thing Thing, the game is in creating the category.

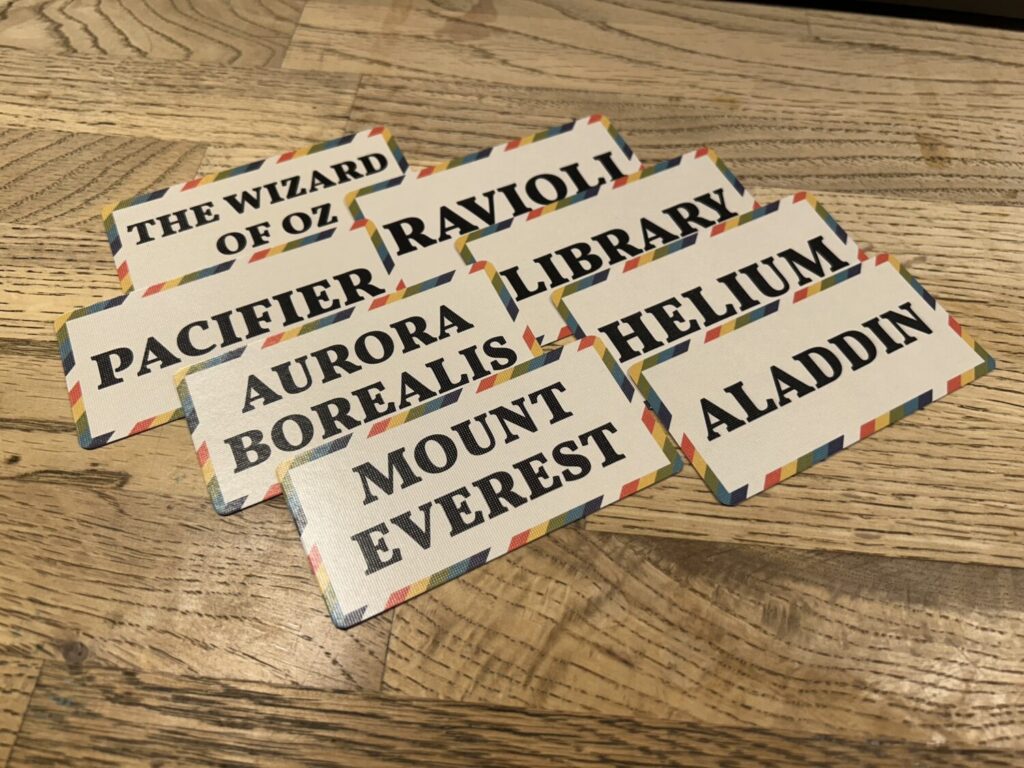

Let’s say my starting hand includes the following cards: The Wizard of Oz, Ravioli, Pacifier, Library, Aurora Borealis, Helium, Mount Everest, Aladdin. My goal is to get rid of as many of my cards as possible, which I do by naming a category that includes two or more of them and playing the appropriate cards. I could easily say “#JustBookThings” and play The Wizard of Oz and Library, or “Nature” and unload Aurora Borealis, Helium, and Mount Everest, but there’s a catch.

After I’ve named my category and played my cards, other players get a chance to play cards from their hands. Let’s say I went with “Nature.” The next player could add Birch Tree to the pile, or Flamingo. Magazine, even, if they’re feeling impish [ed.: Nature is the name of a prestigious science periodical]. That one could backfire. All cards are subject to the table’s discretion. If any player disagrees with a card’s inclusion, it’s out, unless another player vetoes the objection.

After I’ve named my category and played my cards, other players get a chance to play cards from their hands. Let’s say I went with “Nature.” The next player could add Birch Tree to the pile, or Flamingo. Magazine, even, if they’re feeling impish [ed.: Nature is the name of a prestigious science periodical]. That one could backfire. All cards are subject to the table’s discretion. If any player disagrees with a card’s inclusion, it’s out, unless another player vetoes the objection.

For every card that the other players are able to add to my category, I have to draw one card from the deck. In a game that’s all about emptying your hand, a generic category can be a death sentence. Sometimes, often even, it’s best to go with the strangely specific: “Things that could be seen in posters on the wall of Mrs. Martin’s third-grade classroom,” which would let me play Aurora Borealis, Helium, and Mount Everest. Not too shabby, and since it’s unlikely other players would be familiar with Mrs. Martin’s decor, I’m probably safe.

They can take a swing, though. If you have an educated guess, you can make it. There’s no harm in it. Worst case, you take the card back. If you think it’s a reasonable guess that an Elephant or a Sink—“Wash your hands!“—could be found on Mrs. Martin’s walls, you can play it and see.

This is where Thing Thing might lose some people. The game naturally encourages rules lawyering, people making impassioned arguments for and against a card, but it can, with the wrong audience, get bogged down. The social contract rewards pushing the envelope ever so slightly, but it also cannot bear a try-hard. You have to play in good faith. To constantly play cards that belie reasonable inclusion is to try the patience of the other players. To put it another way: if you play Thing Thing as though winning or losing were all that mattered, it will become a miserable experience.

For everyone else, Thing Thing is full of laughter, full of realizations that you should have added a proviso or two to your category. There are three restrictions on categories, all worthwhile, including a note that players can only only use categories having to do with the spelling or form of words once per game. D.V.C. is generally minimalist with rules, to the point that their games are often (intentionally) left up to interpretation, but what rules are there tend to be there with good reason. This rule not only forces players to engage with the creativity the game is meant to provoke, it also means you can win a game by playing two words that fall into “Words that contain an S, an L, and have E as their third letter.” Hypothetically, of course.

Not that winning is what matters.

Cards Against Cards Against Humanity

Thing Thing is a fun game in its own right, but it serves a particular and desperate function in my life: at last, I will never have to play Cards Against Humanity again.

Not that my friends are eager to play that puerile, infantile, hanging chad of a game, that mole on the wrist of humanity. Thank god. But I know people still play. Thing Thing can set them free. It occupies the same space, this associative word game with a high player count that plays faster, fosters more—any—creativity, and rarely lends itself to edgelordish attempts at provocation.

Never again must a dollar be spent on a game that relies on shock to derive any value. We can cast off the shackles of playing a game spent praying/hoping/wishing for circumstance to allow just one—please, lord, just one—instance of humorous coincidence. No longer are we at the mercy of divine providence to drop the perfect Hitler joke in our laps. Hosanna. For that alone, Thing Thing would be worth its weight in gold. That it happens to be a joy in its own right is a nice bonus.