I’m not particularly good at board games.

Now, to be fair, this normally wouldn’t be too much of a burden in most people’s lives. I’m certain that there are legions of men and women who, after being ground under their cousin’s capitalist heel in a game of Monopoly after Thanksgiving dinner, made the

choice to pursue other hobbies. Unfortunately, I’m also a huge fan of board games, with more and more space on my shelves and in my budget gobbled up by this pursuit. And while I’m not particularly good at games, the circle of friends that often join me on game nights are

intelligent, canny, and altogether far too talented at racking up victory points while I watch meekly from third or fourth place.

What’s amazing is that, by and large, I’m okay with this.

I once heard someone say that games were machines in which we invest our effort, and the game outputs fun. In the last decade, as designers have learned more ways to generate these joyous experiences, many games have come out that seem bound and determined to create a machine that produces fun for every player, not just the winner. An experience that gives every player the chance to walk away from the table with a grin on their face, regardless of whether or not they won, is a remarkable one, and I find myself coming back to the few games that manage this time and

time again. So, how do designers manage to find the fun in failure?

Tell Me A Story…

Games are notorious for crafting stories that we find ourselves exaggerating about for weeks after leaving the table. But few have the narrative so deeply baked into the experience that the story that emerges overwhelms nearly every other aspect of the game, including victory. Tales of

the Arabian Nights earned a permanent spot in my collection the first time I played it.

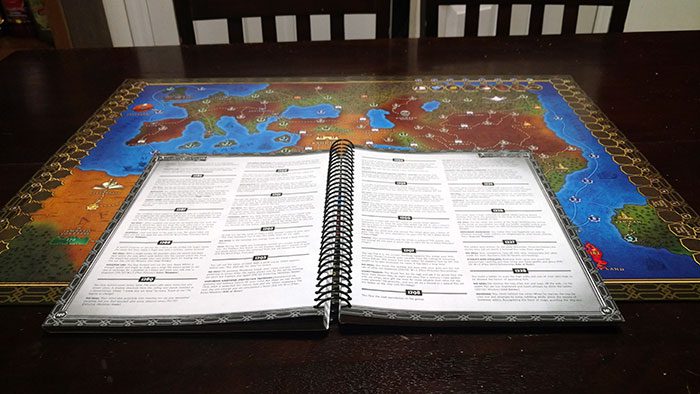

This masterpiece of narrative storytelling looks as if designer Eric Goldberg spent a lazy weekend happily eating his entire childhood collection of Choose Your Own Adventure books before building this

game. The book of tales that comes with this game is massive, looking like the textbook assigned by a cantankerous Ancient Studies professor. (On a side note, there’s a great deal of joy found in seeing first-time players suffer a minor cardiac event when they assume the book of tales

is the instruction manual.)

As you play Tales of the Arabian Nights, your character journeys across the lands made famous in Scheherazade’s thousand and one tales, meeting princesses and thieves, battling diabolical djinn and rampaging elephants, and discovering barrels of fine wine or misery and heartache. A

mechanic that assigns certain traits to each player, including Accursed, Beast Form (nope, not kidding), and even Sex Changed (still not kidding), creates a personalized and unique experience as you traipse across the board.

In my first game of Tales, I tried to rip off a Sultan by passing off a fake necklace as a priceless family heirloom. Seeing through my deception, he ordered his men to drag me outside and beat me handily, leaving me crippled and destitute. Taking pity on me, a woman took me in, and we

eventually married. Of course, the lure of the unknown (and the fact that it was my turn) saw me departing my beloved, and I soon found myself stuck to the side of the feared Magnetic Mountain. After breaking free, I got transformed into a goat, kidnapped by bandits, and had my gender

spontaneously switch after dipping a toe in a shimmering lake. At that point, who was winning the game was the least interesting thing about it, and we couldn’t wait to get it back to the table.

This isn’t an easy needle to thread. Other games, such as Above and Below and Seafall, have attempted to provide these customized narratives, but haven’t quite managed to generate that bizarre and unique experience. But in those rare games that can give me a story to tell, I

can be in last place, and won’t care in the slightest.

We’re All In This Together

As much as I adore Tales of the Arabian Nights, I have some friends who despise that game. They’re the hypercompetitive gamers, the ones who find great joy in burrowing deep into the mechanics of the game to wring every last possible victory point. I used to think that winning was

all that mattered to this type of gamer, but it runs deeper than that. If winning is all that matters, a simple coin flip will get you to the winner/loser paradigm you crave so deeply, all for the low low cost of 25 cents (if you flip a lesser denomination coin, you are indeed a

Communist).

The reality is that a simple win/lose proposition is so much less interesting than a Gordian knot of mechanics, a tapestry of design that offers up a tantalizing puzzle to those who sit down at the table. These games taunt the players, daring them to tease out the precise combinations

and tactics that will produce victory. When these games are cooperative, it challenges each and every person at the table to bring their own intelligence, experience, and canny to the game, and creates a shared experience. Failure, in this type of game, is then shared among the group, and

assigns the game a type of daunting reputation that it previously lacked.

For my gaming group, no game better exemplifies this than Antoine Bauza’s demented masterpiece Ghost Stories, a cooperative game that sees players taking on the challenge of monks defending a village against a phalanx of rampaging poltergeists. Ghost Stories is a brutal,

overwhelming experience, a game that puts your back against the wall from the very start, and grinds away your resources in a nonstop onslaught. Our first five games of Ghost Stories saw us completely crushed. But instead of seeing this as a demoralizing experience, these failures began to

paint the game in a different light.

Ghost Stories sat on my shelves, mocking me. When I walked past in the morning to get breakfast, it smugly reminded me of my monk failing two rolls in a row and getting torn apart by a particularly nasty combination of ghosts. When I came home from work and perused the shelves for a

quiet evening game with my wife, it was there with a condescending, “No, no, you’re right. Castles of Mad King Ludwig is much more appropriate for your skill level. Maybe a little Chutes and Ladders? I think that copy of Candyland you played with your daughter eight years ago

might still be upstairs…”

There are many, many people I know who cannot stand Ghost Stories, and it’s hard to blame them. Getting smacked around your gaming table by the schoolyard bully of board games can be a fairly disheartening experience. But for some, it inspires them to set their jaws, gather their

friends, and charge howling into battle. Those failures become part of your tale, the long, slow simmer that makes the final meal that much more tender and delectable. When you do finally win, not a single one of you will leave those lost games out of the story you tell.

Why I Oughta, or “The Three Stooges Effect”

As a kid, I went through a phase where I was obsessed with Jackie Chan films. I adored his films, and watched raptly as he flipped and kicked his way through legions of one-dimensional foes, but my favorite part was the credits. As the names of gaffers and assistant to the associate

tertiary director’s aide scrolled past, the blooper reel rolled, and I got to sit and howl with laughter as Chan and his co-stars slipped and stumbled across the screen. Failure, in the right context, can be hilarious, and many game designers have figured this out.

Galaxy Trucker is a game by the extraordinary Vlaada Chvatil that sees players building spaceships. Well, “spaceships” is a bit generous. Think the spacefaring version of the car in which the Clampetts sputtered into Beverly Hills, complete with a crew of about the same

knowledge level. You assemble your spaceship from discarded space junk, leaving open holes in your hull, lasers pointing haphazardly in all directions except for those that might actually do some good, and half a dozen shield generators with enough power to drive exactly none of them. You

then take this cosmic jalopy and send it hurtling into pirates, asteroid fields, and other galactic hazards, and pray that some piece of this engineer’s nightmare will come coughing its way into spaceport in a cloud of exhaust and shattered dreams.

The reason Galaxy Trucker doesn’t send the players into spasms of table-flipping rage is that you’re all in the same horrible, horrible boat together. Yes, a pirate just blew up my only remaining cargo compartment, and yes, that compartment was the only thing holding a

quarter of my ship onto the rest. But my turn through the ringer is done, Jen’s now at the head of our convoy, and an asteroid big enough to send Bruce Willis sprinting back to his oil rig is about to turn the entire front half of her spaceborne 1987 Nissan Stanza into a cautionary

tale to scare teens out of drunk driving. You’re all failing miserably together, and even the instruction manual encourages this. Chvatil includes a step to the game that involves you all mocking everyone else’s spacefaring monstrosities, and explains that if you managed to come

out of this clutching even a single space buck in your trembling, traumatized hands, you’re a winner. It’s one of the funniest experiences in board gaming.

Dexterity games such as Catacombs and Flick ‘Em Up are built around this idea. Flicking a disc is a surprisingly difficult endeavor, and while it’s satisfying to thread the needle between two wooden cacti and drill your opponent’s cowboy from five feet away, it’s

much funnier to the rest of the table when you fail miserably. By the end of these games, you’re watching your opponents take their turns with maniacal glee, waiting for them to miss their target and sent a wine glass tumbling to the floor, because those are the moments that make

those games genuinely delightful. Games that pose a ridiculous, absurd challenge that all of you have the opportunity to fail equally at can be one of the more memorable experiences you can have at the table.

Winning a game will always be a rewarding experience. But if you limit your enjoyment of games exclusively to the ones you win, there’s a lot of joy that will pass you by. Board games today are this brilliant, inspired collection of ideas and experiences, built to reward every

single person who grants them a few hours of their time. Those games that understand that are always going to find their way back to the table, and manage to provide something wonderful for those who are failing their way through the turns.

What do you think about Finding the Fun in Failure? Give us your opinions in the comments below!

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive periodic updates about news, articles, and contests.

Add Comment